Load, Ready, Fire!

During the Civil War it took eight men to fire a cannon. (Women were not allowed in the Army, so all soldiers were men. If a woman was found in the ranks, she was sent home). The men on a cannon crew were numbered one through seven, plus a gunner. The gunner was in charge. Numbers one through four formed a box around the cannon, facing the direction the cannon was pointed. Numbers five, six and seven were posted behind the limber box, which contained the ammunition. The gunner stood between the cannon and the limber box and somewhat to one side or the other.

The gunner gave the command, “Attention detachment!”, and all the men came to attention. He then announced, “By detail load.” This meant each step would be called out in detail until the men became more comfortable with the process. “Take implement,” meant number one was to take the sponge/rammer out of its hanger. “Clear the piece,” meant numbers one, two, three and four were to turn and face the cannon, and number three was to place his thumb over the vent hole at the rear of the cannon to prevent air from entering the cannon tube during the clearing process. Number one dampened the sponge head, inserted it into the muzzle of the cannon and pressed it in until it reached the back of the barrel, at which time he turned the sponge two full revolutions. Cannons fired black powder contained in cloth bags, and after firing there was the risk of burning cloth or powder remaining in the barrel, hence the need to extinguish the burning items with the sponge.

After number one removed the sponge, he said, “Piece clear,” which was echoed by number three to the gunner. The gunner announced the range of the target and the type of projectile — for example, “Shell, 1,100 yards.” Number six removed a shell from the limber box and set the timed fuse for the correct number of seconds to cause the shell to explode at a range of 1,100 yards. For a 10-pound Parrott rifle, that would have been 3.25 seconds. The shell and powder bag were placed in a leather gunner’s haversack, carried by number five, who advanced toward the gunner. The gunner inspected the projectile for proper type and fusing. He commanded, “Advance the round,” upon which number five approached number two. Number two removed the powder from the gunner’s haversack and inserted it into the muzzle of the barrel, and the gunner commanded, “Ram.” Number one carefully rammed the charge all the way to the back of the barrel, taking care to place himself behind the muzzle as much as practicable. After number one withdrew the rammer, number two inserted the projectile, the gunner again commanded, “Ram,” and number one rammed the projectile back against the powder.

Number five returned to the limber box, and numbers one and two each stepped to their side of the cannon. The gunner ordered, “Ready,” and number three inserted a brass wire into the vent to pierce a hole in the powder bag. Number four inserted a friction primer, that is, a brass tube containing fast-burning powder and a friction compound similar to the head of a farmer’s match, into the vent hole and attached a rope, called a lanyard, to the primer. Number three placed his left hand firmly on top of the vent hole and primer while number four took up the slack in the lanyard. When number four was in position, number three stepped away from the gun, taking his hand off the vent and primer. The gunner yelled, “Fire,” and number four pulled the lanyard, which ignited the friction compound, igniting the fast-burning powder, which sent flame into the bag of powder inside the cannon. That bag of powder exploded, causing the cannon to recoil six feet and sending the projectile toward the target. The fuse of the projectile was ignited by the exploding powder bag, and 3.25 seconds and 1,100 yards later, the shell exploded.

During the Civil War, the Army had all of this in its manual, the same way your financial institution should have its procedures written out. Imagine the calamity that would ensue if one of the steps were taken out of order! Thankfully, if your financial institution does not have procedures documented, it won’t result in loss of limb or life, but it can still be catastrophic in different ways!

The Army required each man on the gun crew to learn all the steps for all the positions, so if one or more persons could no longer service the gun, the cannon could continue firing. The Army had actual reassignments of duties to allow the cannon to be fired with anywhere from one to eight soldiers — the same way your financial institution should have a succession plan and a disaster recovery plan!

If you don’t have written procedures, cross-training, a succession plan or a disaster recovery plan and would like help with developing them, email your Wipfli relationship contact. And if you do have these things and want them tested or enhanced, please call or email us.

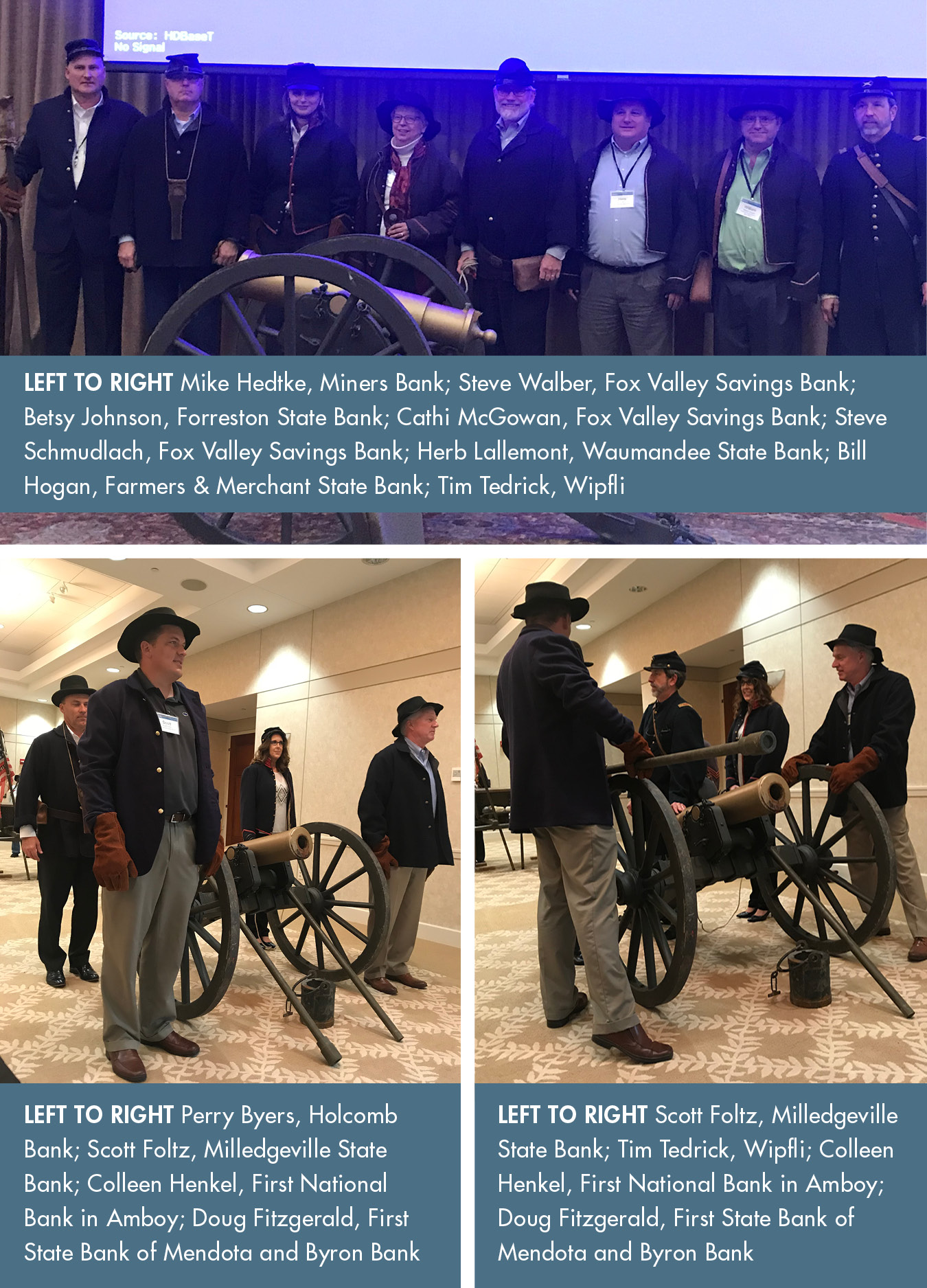

We recently shared this team-building session at our Community Banking Forum. Enjoy the photos of some of the bankers who participated below.